During China's planned economy period, a time aimed to mitigate the impact of the shortage of goods (which it is important to stress that scholarly literature establishes that, at least in the early stages, it was the shortage of goods that necessitated a planned economy, and not that a planned economy resulted in shortages), the government implemented a system of planned supply to ensure a balance between supply and demand. Economically, to guarantee that both urban and rural residents had access to essential daily necessities such as food, clothing, and other basic items, the state issued specialized purchase vouchers based on population figures. These vouchers included grain tickets and cloth tickets, which, along with other items of similar nature, are classified under the umbrella term “exonumia”.

This system was crucial for maintaining order in a time when resources were limited. Each household received a certain quota, enabling them to purchase only what was allocated. In all fairness, this method of distribution ensured that everyone received basic supplies. However, a rigid command economy meant that, in many cases, the needs and wants of the average citizen—referred to as "consumers" in economic terms—could not be met if those specific needs were not included in the state’s planning. As the economy and its productive forces evolved, this system limited the variety and quantity of materials available, significantly restraining the improvement of living standards for the Chinese people.

This lack of responsiveness to consumer demands led to widespread dissatisfaction, as citizens struggled to access essential goods. The restrictive nature of the command economy stifled innovation and entrepreneurship (which during most of the Mao Era was considered to be against the “tide of history”). Ultimately, the potential for a more dynamic and responsive economic framework remained unrealized. For this reason, government-related exonumia (particularly rationing tickets) gradually faded during the 1990s, specifically after Deng’s Southern Tour of 1992 that called for the expansion of the private sector.

This section will also explore other “tickets” that are not in the traditional exonumia sense.

Exonumia - Finance and the Economy

Finance and economics in the Mao and Post-Mao Eras were turbulent, and its evolvement was guided by the changing economic policies and the balancing between “private” and “public” in the transitionary state of late capitalism (which to a large extent was not completely realized and fully developed by its official termination in 1956) and early socialism.

From 1949 to 1953, the PR China was still in the momentum of the capitalistic development of the Republic of China, and thus, at least in the cities (the rural areas were subject to the CPC’s Land Reforms), capitalism, in all its forms, continued to develop. Though there was widespread fear among the bourgeoisie that the new communist government would take forceful measures against them, this was not the case for the early years of the PR China.

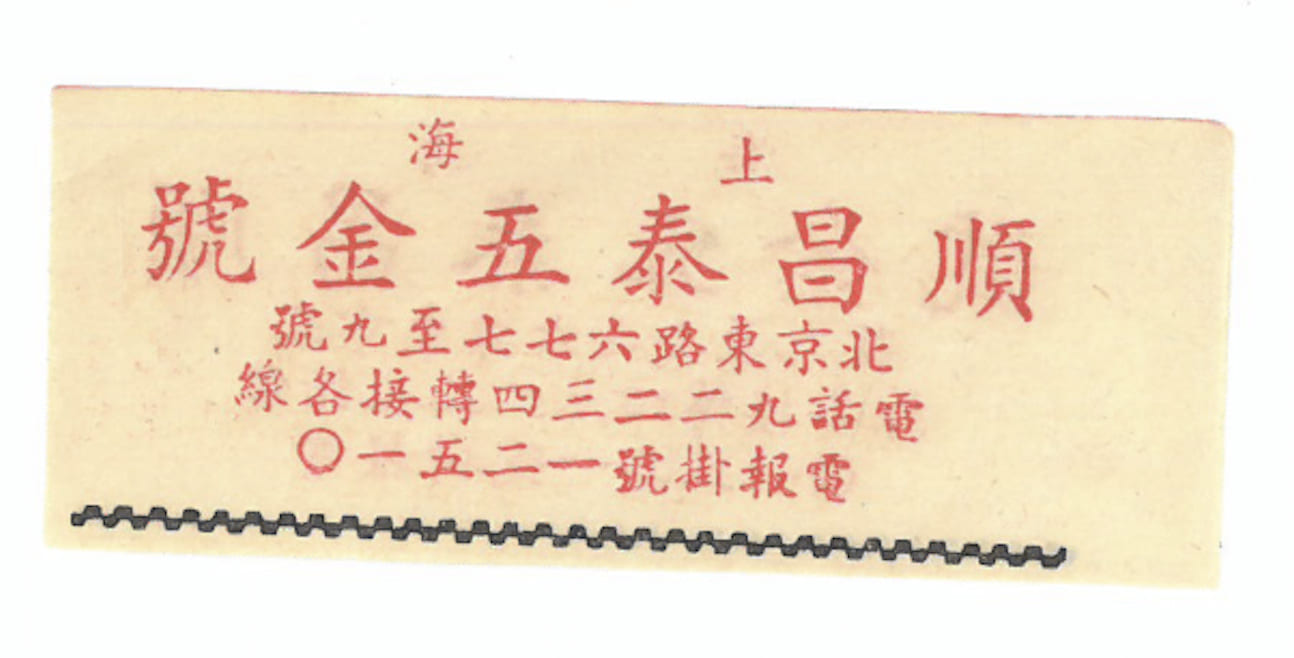

An advertisement for a private utility store in Shanghai in the 1950s (The date is evident as the Chinese characters have yet to be simplified and the characters are still read from right to left).

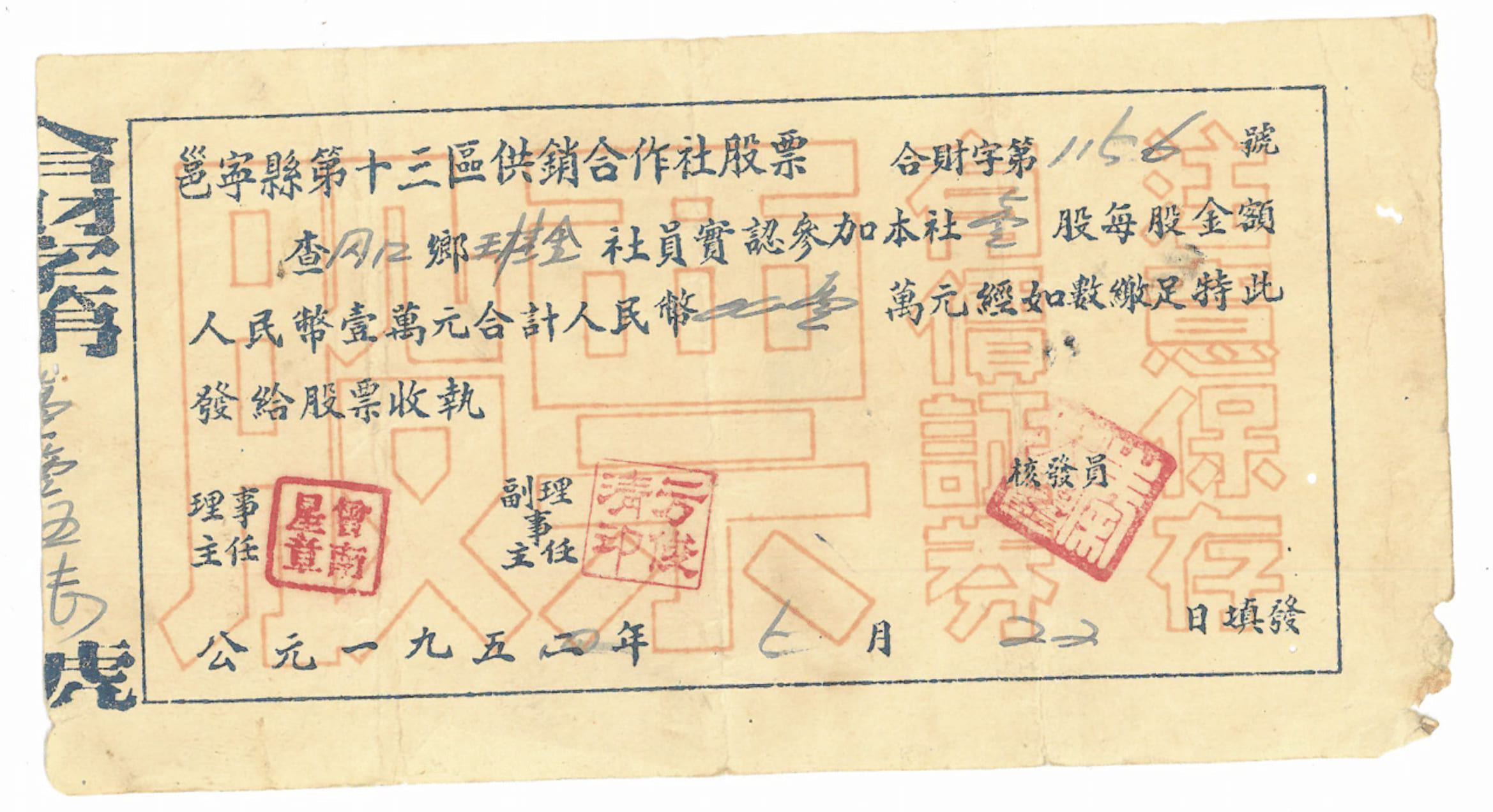

A stock holding at the "supply and marketing cooperatives" dated 1952. The holders of stock at virtually all co-ops during the 1950s could collect dividends accordingly. This was the approach that China took in collectivizing the economy, where in most cases, instead of forceful seizure and redistribution, the state would gradually buy out the private sector.

In 1953, after the successful completion of the Rural Land Reform, the CPC turned its attention to further transforming the economy and enabling China's advancement into the early phases of socialism. From 1953 to 1956, China underwent the Three Great Remolding, during which agriculture, the handicraft industry, and the capitalist industry and commerce were gradually transformed to collective ownership or a hybrid between private and public ownership.

From 1958 to 1962, China entered the Great Leap Forward. The Great Leap Forward was the Chinese attempt to accelerate industrialization and agricultural collectivization and mechanization. However, its accelerated nature sowed the seeds for its inconsiderateness that eventually led to economic disruption and hardships, especially when combined with the Three Years of Natural Disaster (1959-1961).

Though a period of economic revitalization, symbolized by the Seven Thousand Cadres Conference, followed the termination of the Great Leap Forward, it was relatively brief and was again disrupted with the launching of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1977). Scholarship commonly depicts the 10 years of the Cultural Revolution as disastrous for the economy. The economy was heavily involved in politics, and many politically undesirable industries and economic activities were terminated or heavily restricted. Despite this widespread conception of economic downturn, for most years, the economy was able to grow and key scientific breakthroughs such as the hydrogen bomb of 1967 and the Dong Fang Hong 1 satellite of 1970.

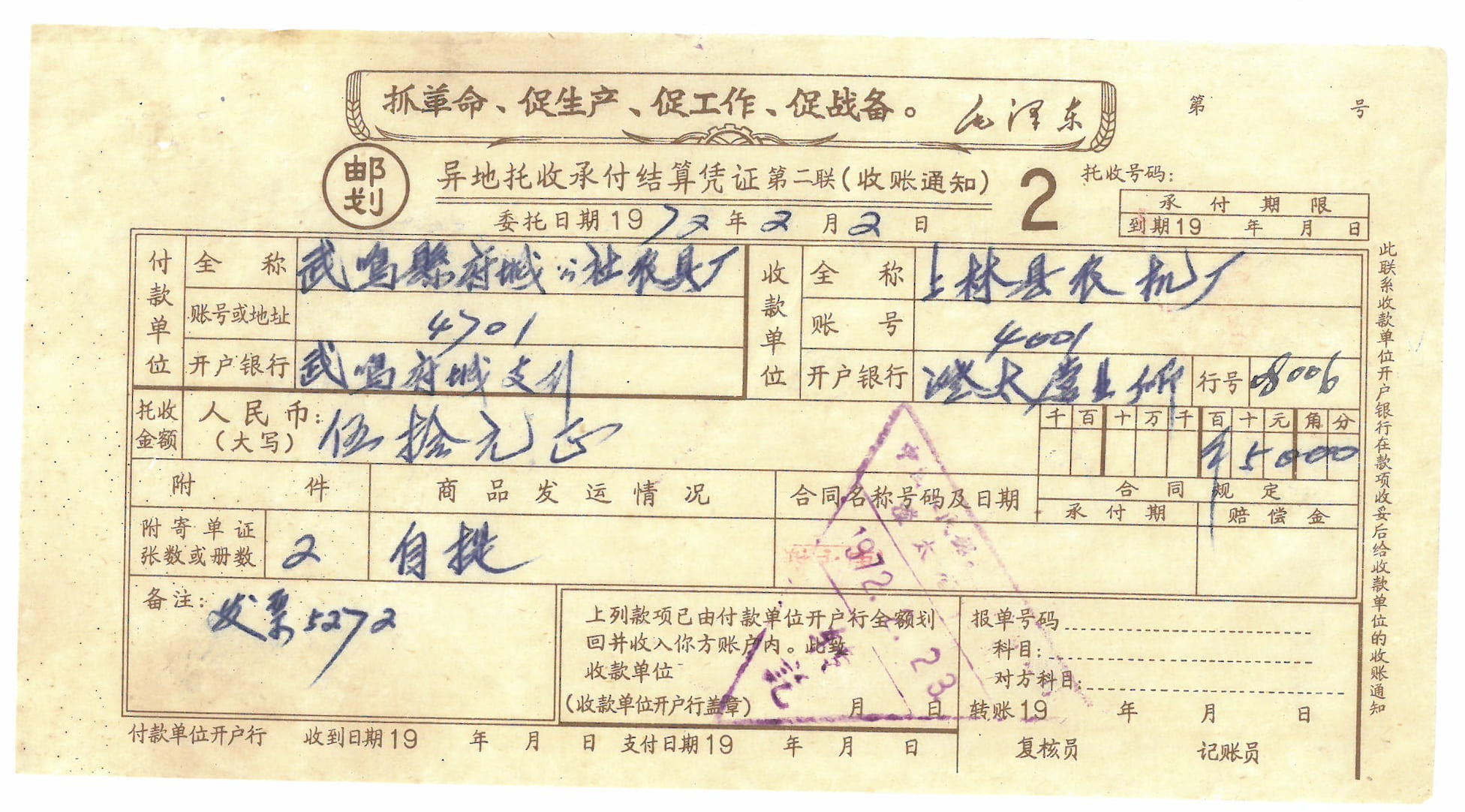

A cash-transfer check for material purchases dated February 2, 1972. The the top of the check is a Quotation of Chairman Mao that reads, "Tighten revolution, speed-up production, speed-up work, and speed-up the preparation against war". The check details a purchase of agircultural tools by one factory from another.

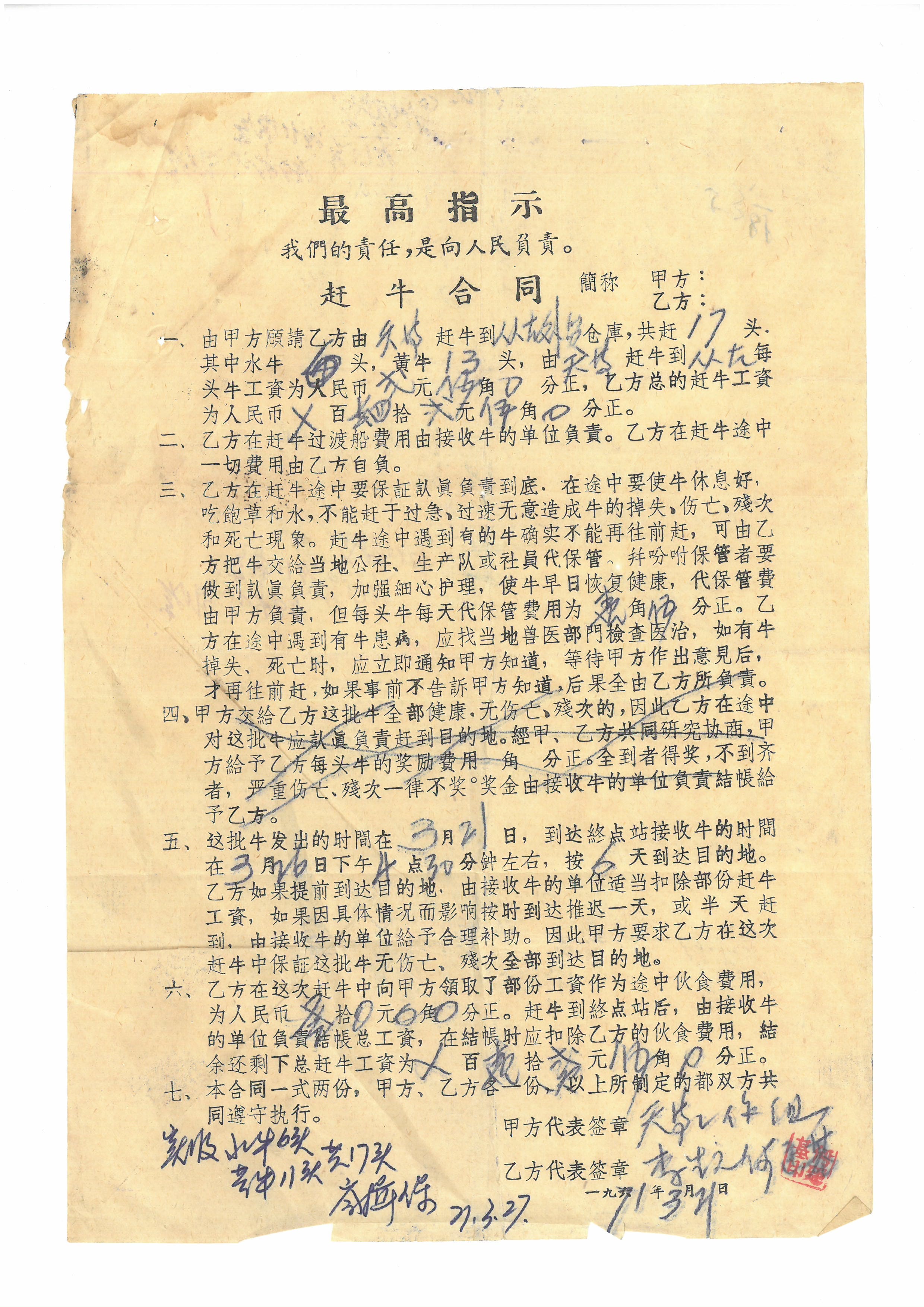

A contract that is official titled "Contract for the Herding of Cows". The contract is dated March 27, 1971. The top of the contract contains a typical Cultural Revolution "Highest Command" by Mao that reads, "Out responsibility" is to be responsible to the people. The lower half of the contact detials the exact timeframe and payment of the herding of these cows.

A state-run "supply and marketing cooperative" (1).

A state-run "supply and marketing cooperative" (2).

Exonumia - Rationing Stamps

In the context of Mao Zedong's era, the Chinese economy was characterized by severe material shortages and limitations, which necessitated the establishment of a rationing system for essential goods and services. This system encompassed a wide range of items, including food, clothing, and household necessities, effectively regulating access and distribution in a context of scarcity. Citizens were allotted a specific quota of rationing stamps that dictated what they could purchase, creating a framework where basic needs were met through a controlled allocation process rather than market dynamics. This system was emblematic of the central planning approach of the time, reflecting the challenges of a primarily agrarian economy striving for industrialization.

However, with the onset of the Reform and Opening Up policy in 1978, China began to undergo a fundamental economic transformation. As production levels increased and the economy shifted toward a market-oriented model, the ticketing system became increasingly obsolete. By the 1990s, rising production capabilities and improved supply chains rendered the ticketing system unnecessary. The gradual phasing out of this system marked a significant transition in Chinese society, symbolizing a move towards greater consumer freedom and the burgeoning market economy that would define the country’s rapid growth in the following decades.

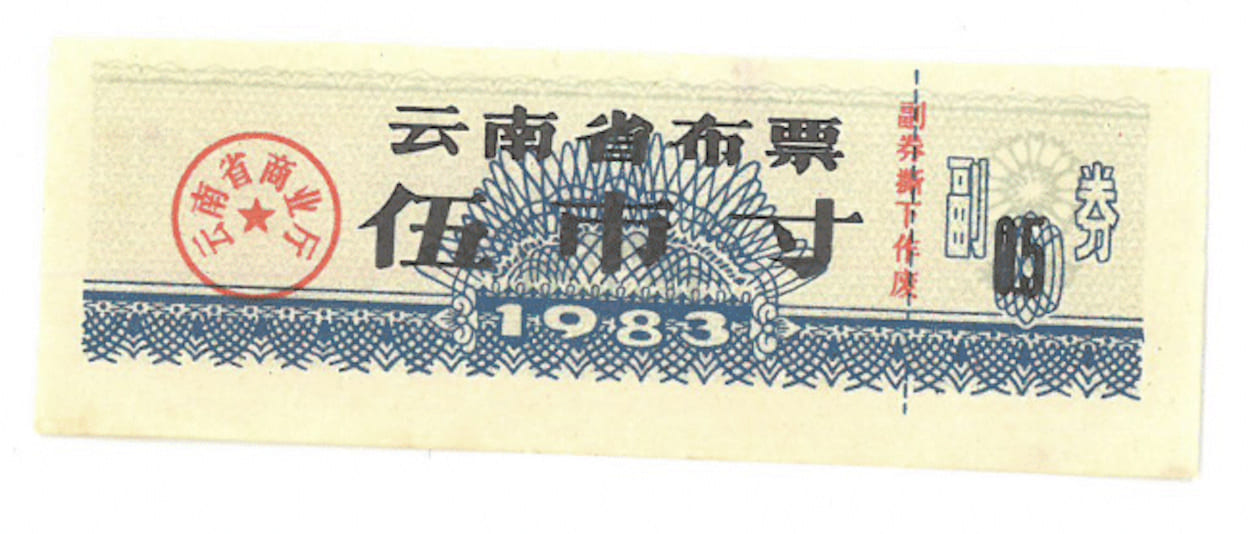

Yunnan Textiles Ticket, 5 Chinese Inches, dated 1983. Issued by the Ministry of Commerce of Yunnan Province.

Qinghai Province Grain Tickets, half a kilo, dated 1975.

All-China Gasoline Ticket, 50 kilograms, dated 1984.

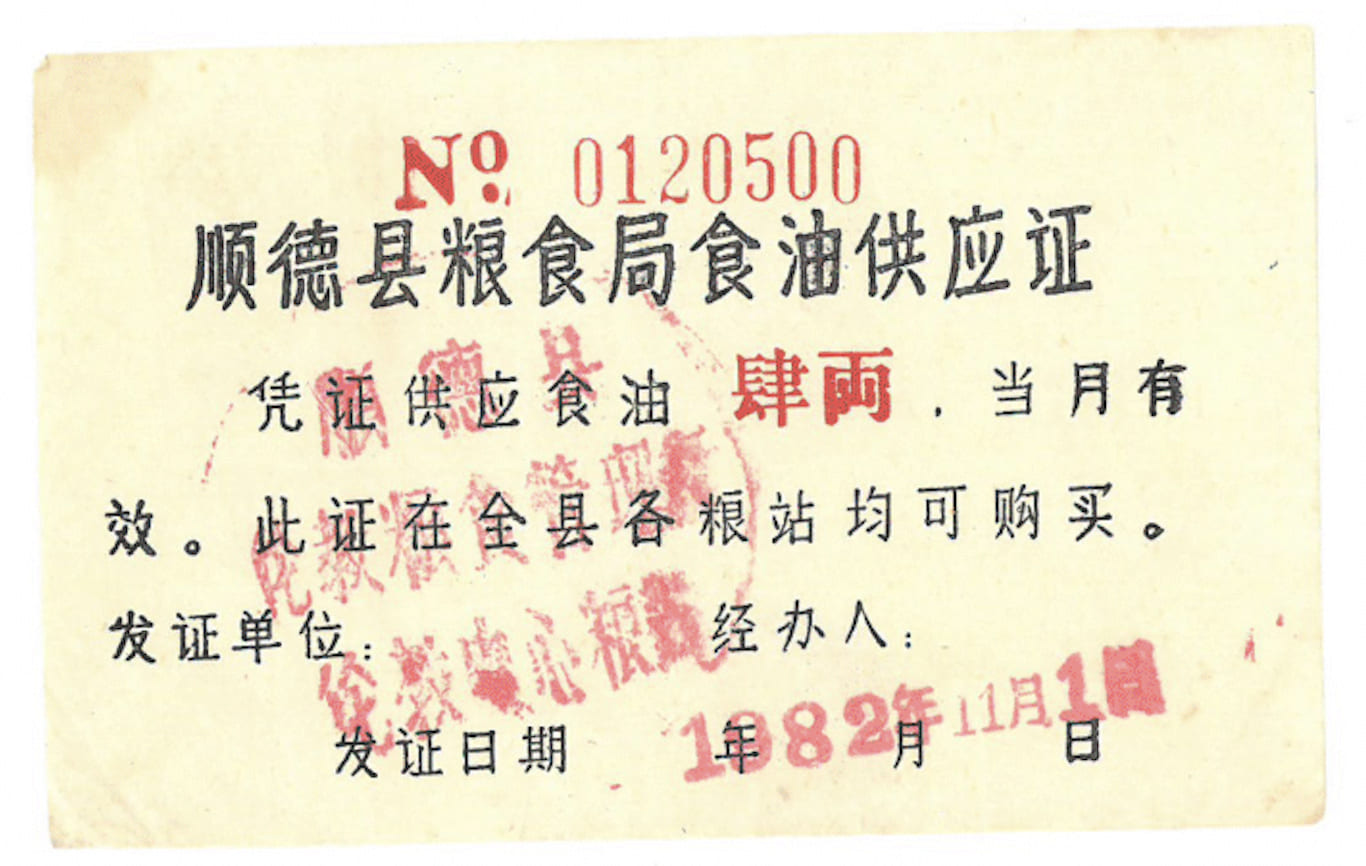

Shunde County Cooking Oil Tickets, 4 liang (0.2 kilograms), dated November, 1982 (the ticket is valid for the issuing month only).

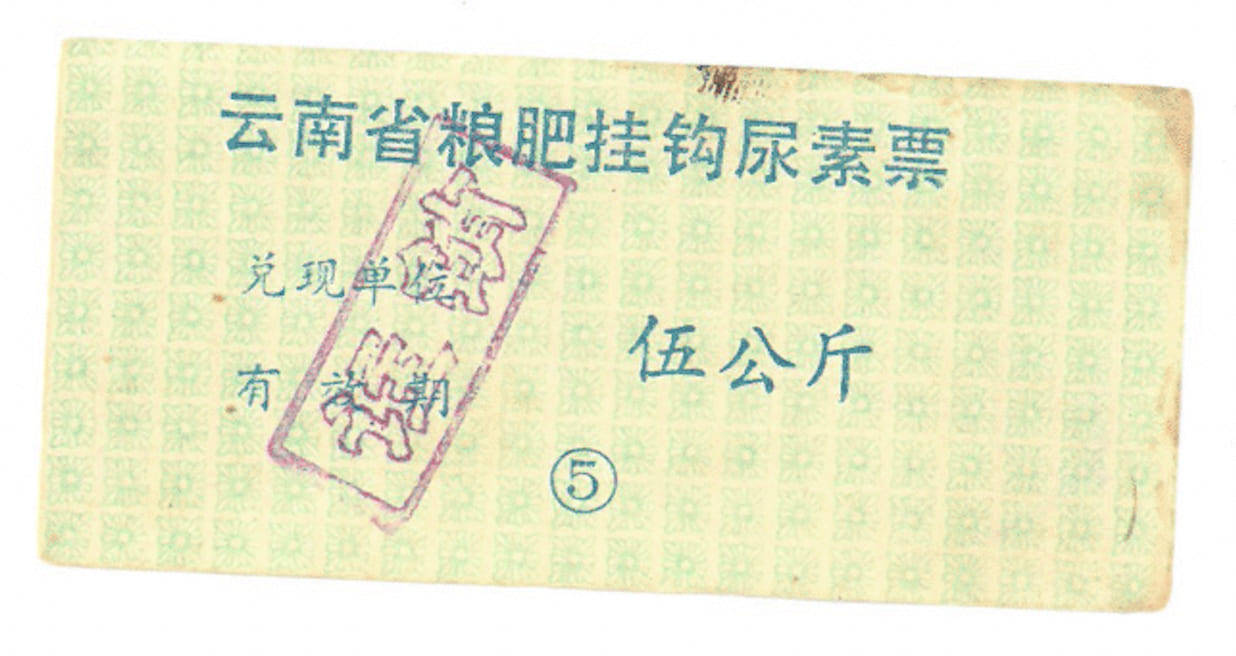

Yunnan Province Urea Ticket, 5 kilograms. The purple stamp signifed that the ticket has been "discarded".

Guilin City (within Guangxi Province) Coal Tickets, 24 pieces of coal, dated November, 1992.

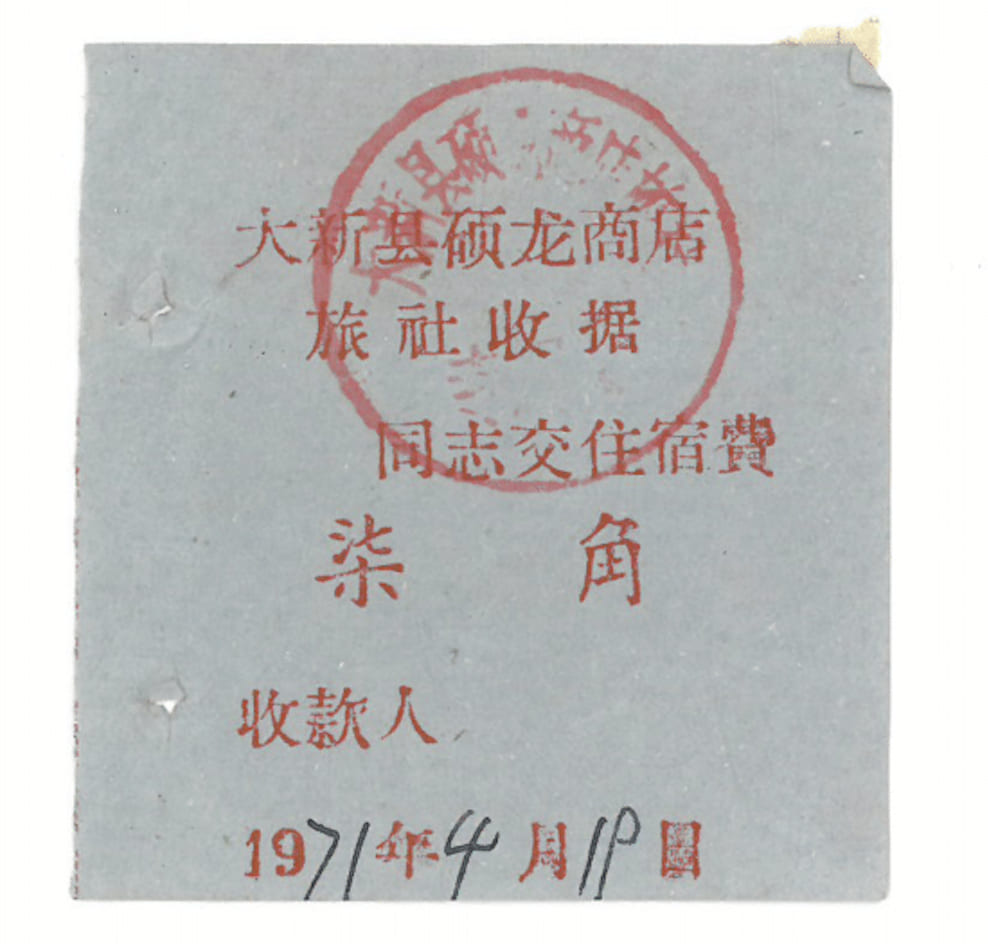

Daxin County Hotel Ticket, 7 Jiao (0.7 Yuan), dated April 19, 1971.

Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Textile Tickets, each ticket is worth 5 Chinese Feet, dated 1973.

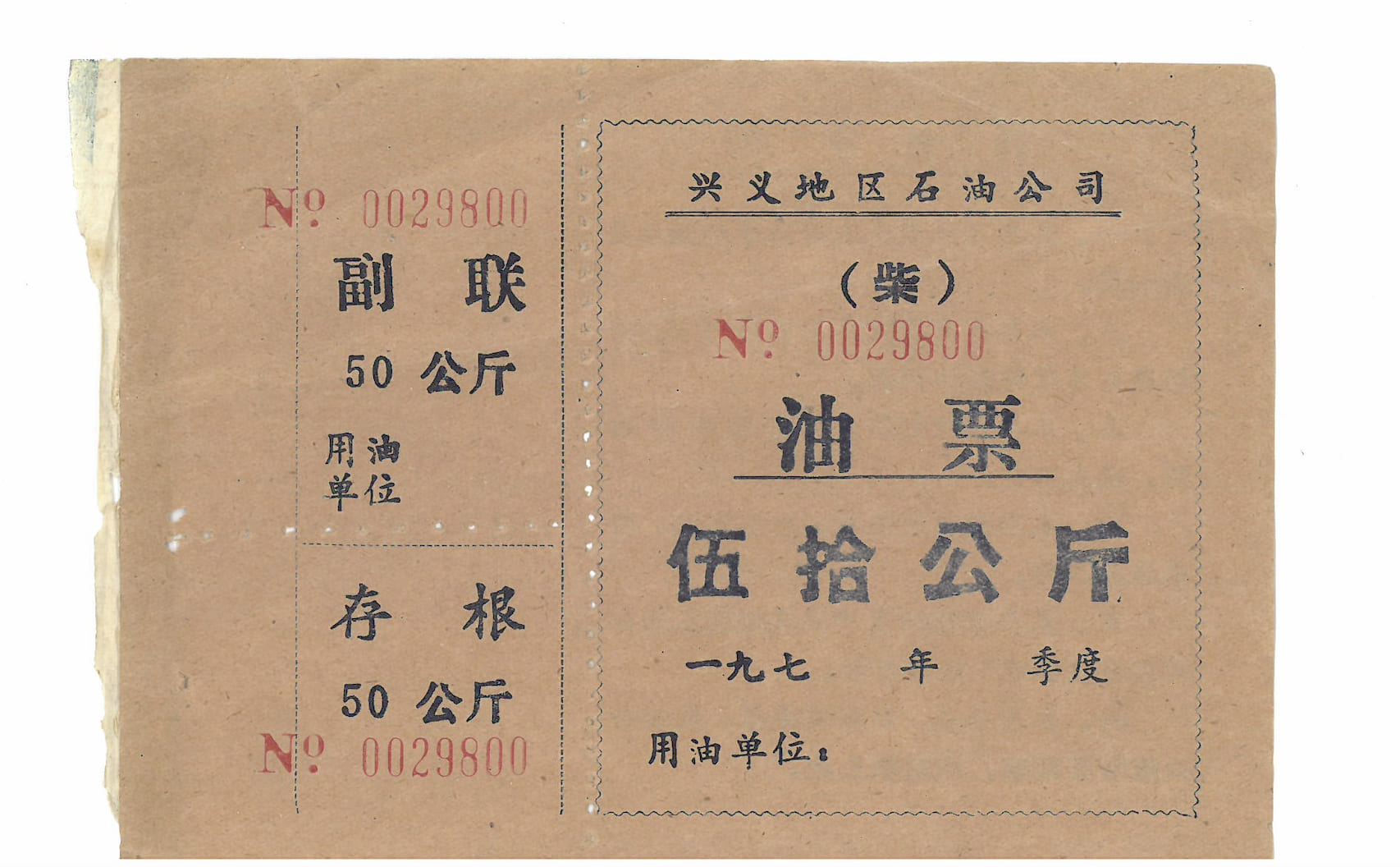

Xingyi Area Diesel Tickets, 50 kilograms, dated 197_.

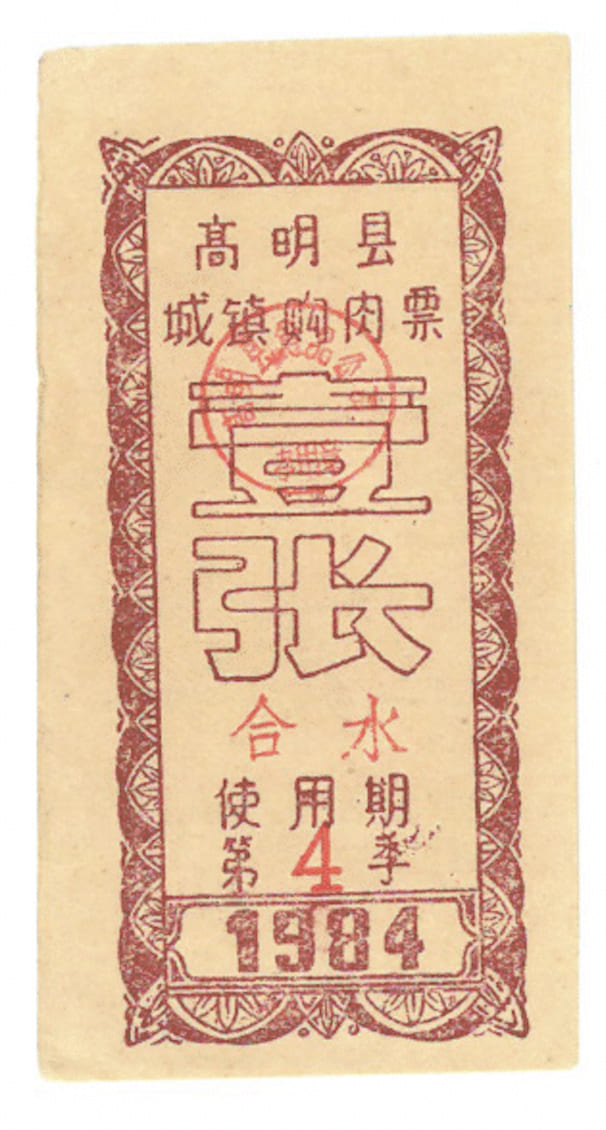

Gaoming County City and Towns Meat Ticket, no specified quantity, dated fourth quarter of 1984.

Kunming City (within Yunnan Province), 12 District Bean Products Ticket, no specified quantity, dated 1984.

Exonumia - "Tickets"

Though tickets are not typically categorized as exonumia in the same vein as the other aforementioned artifacts, they nonetheless occupy a significant place within the broader context of exonumia, particularly in the setting of Mao Era Chinese society. These tickets were not merely functional items; they represented a complex system of resource allocation during a time of scarcity and central planning. The tickets encompassed a variety of forms, from straightforward vouchers that allowed citizens to purchase essential goods like rice or cooking oil, to more symbolic tickets that conveyed political or social status.

For instance, certain tickets could grant access to exclusive events or resources, symbolizing the implicit ideological and social hierarchies prevalent during that period. In this way, tickets served as more than just practical tools for navigating daily life; they were imbued with meaning and significance, reflecting the political climate and societal values of the time. The use of tickets highlighted the intricacies of life of the Mao Era, where access to basic necessities was tightly controlled and often tied to one’s social standing. Thus, while tickets may not fit neatly into traditional definitions of exonumia, they represent a unique intersection of utility and symbolism within the historical narrative of China during the Mao era.

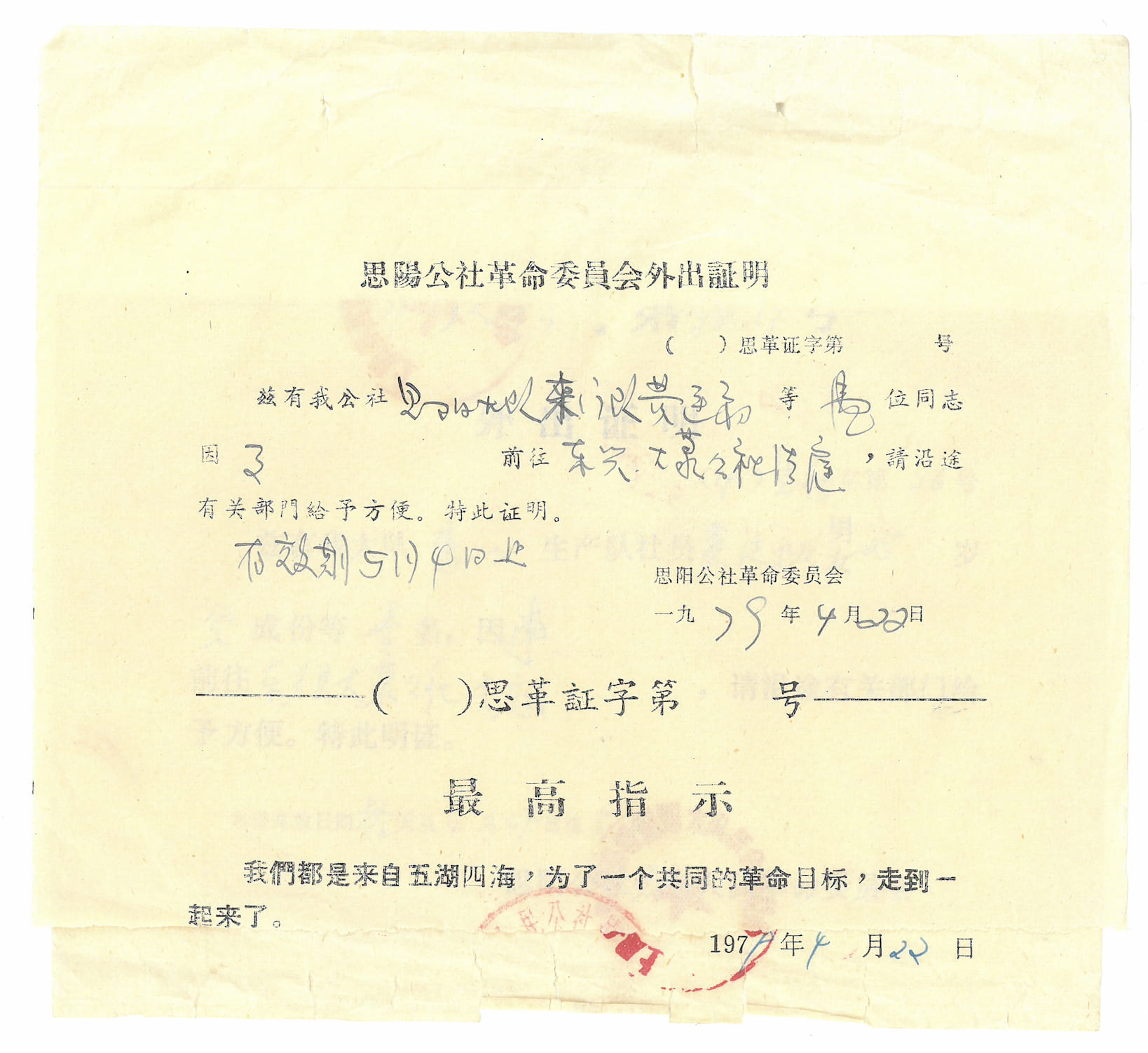

Siyang Commune Member Travel Ticket (as proof that the holder is a member of the commune and is allowed to travel), dated 1979. The bottom text is a "Highest Command" that reads, "We come from the five lakes and 4 seas [meaning around China], but we are united with a common revolutionary goal, and we thus walk together".

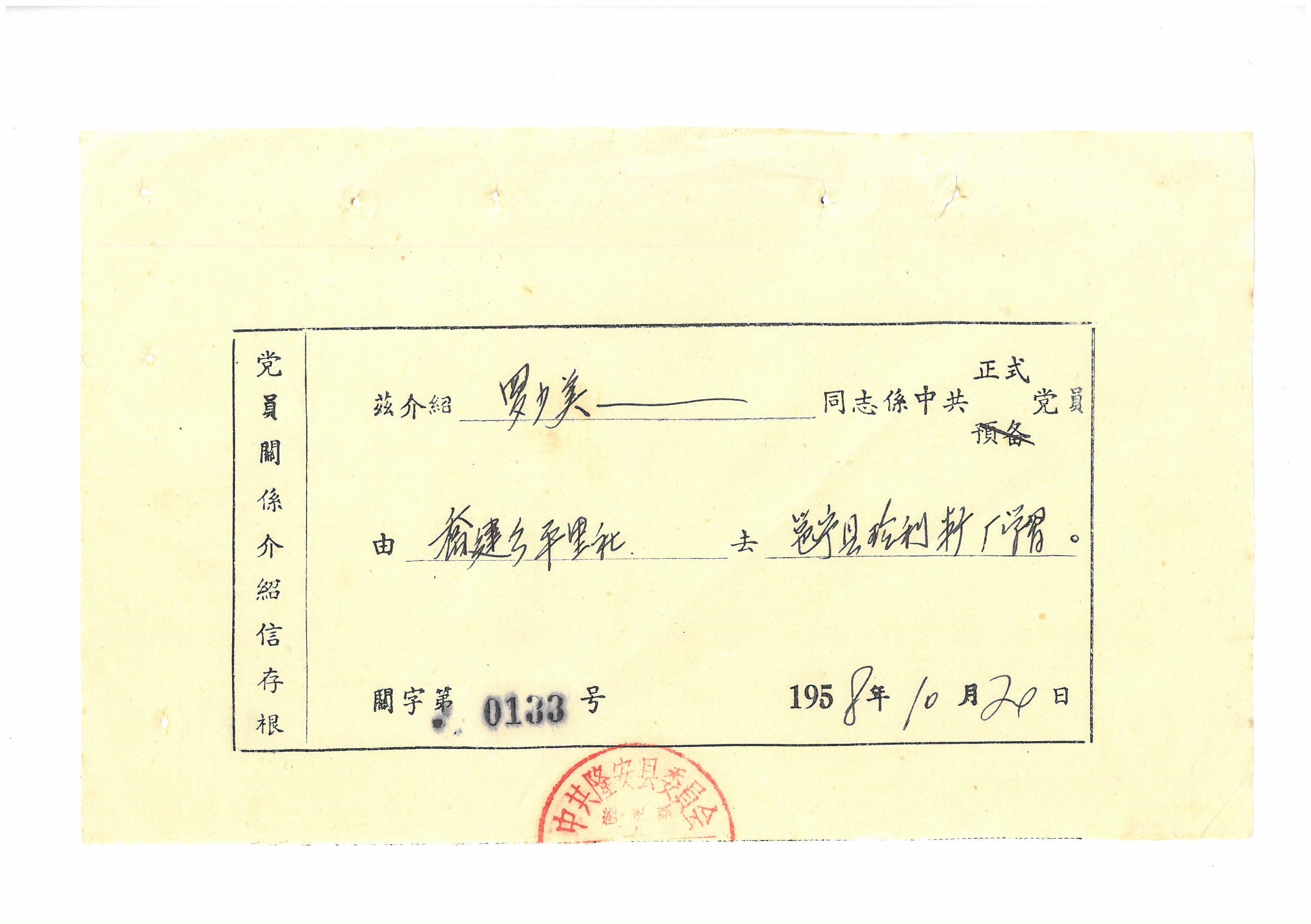

CPC Member Travel "Ticket", dated 1958. The ticket is a "ticket" in the sense that it is a travel reference letter that provides proof for the holder's membership in the CPC and travel destination.

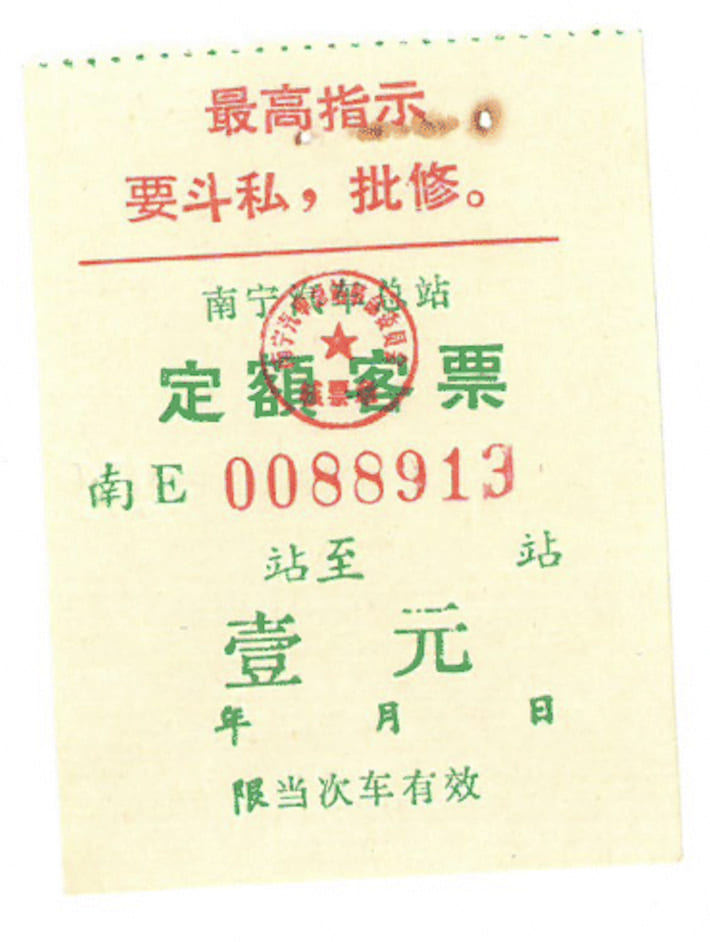

Nanning City Car Ticket, 1 Yuan. The top "Highest Command" reads, "We must fight private ownership and criticize the revisionists."

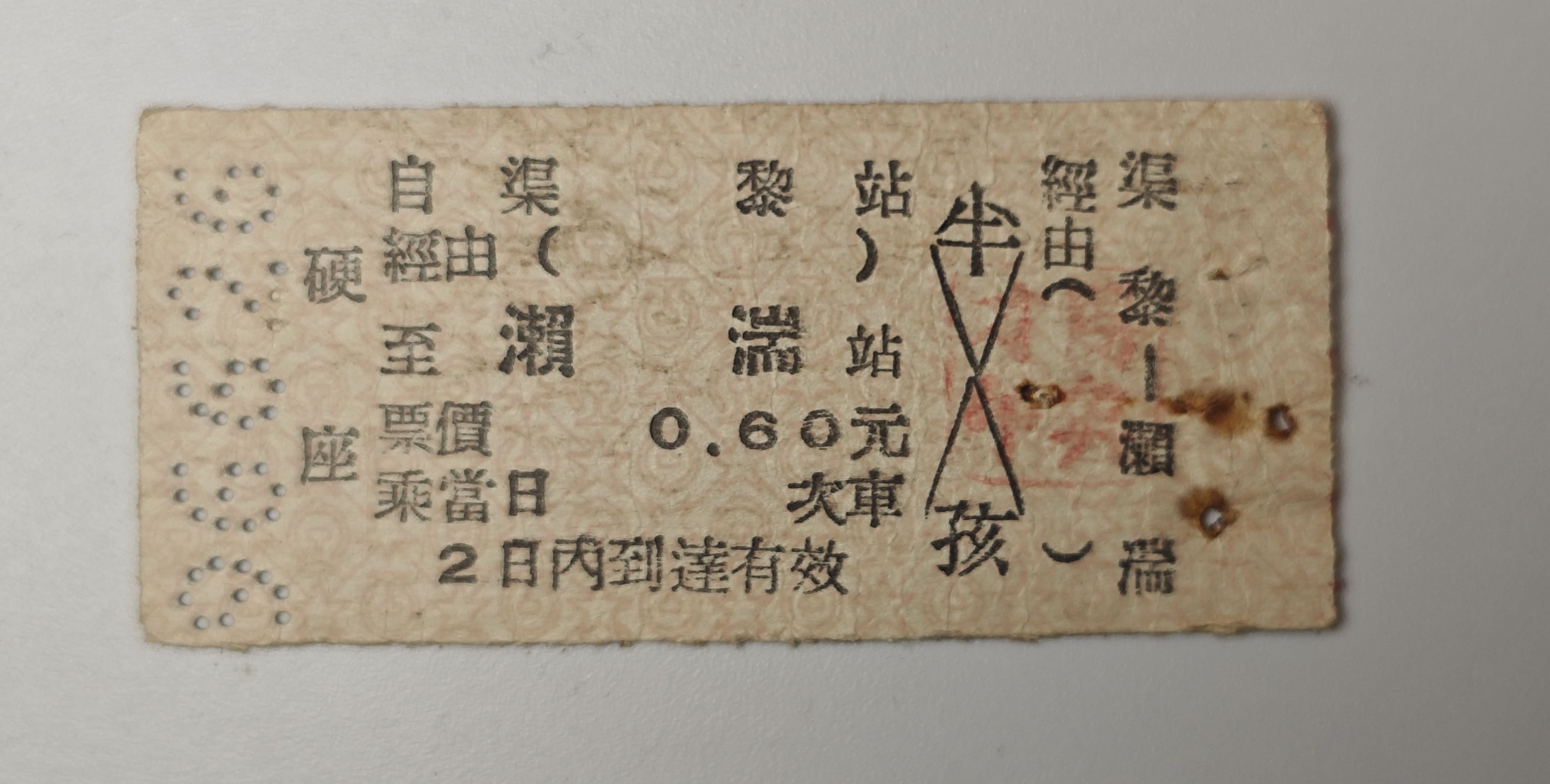

Train Ticket for a Child, 0.6 Yuan.

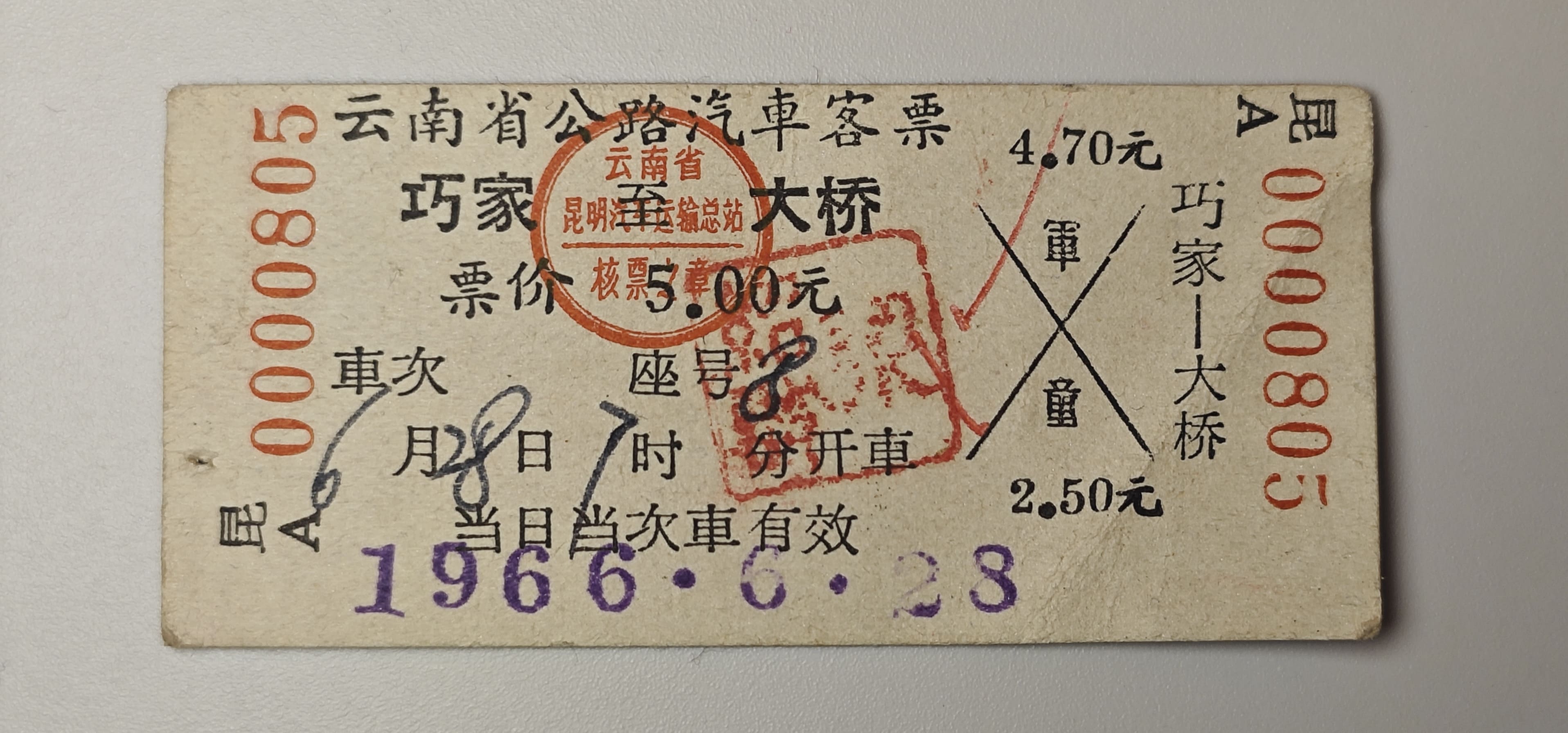

Yunnan Province Bus Ticket for a Child of a Military member, 5 Yuan, dated June 28, 1966. The ticket is from Qiao Jia to Da Qiao.

Exonumia - "in Modernity"

Rationing in China officially ended in the 1990s, marking a significant shift in the country’s economic landscape as it transitioned from a command economy to a more market-oriented system. Following the economic reforms initiated in 1978, China experienced rapid growth, particularly after pivotal moments in 1992 and 2001, when it joined the World Trade Organization (WTO). These milestones catalyzed a transformation that encouraged foreign investment, increased production capacities, and expanded consumer markets.

China's entry into the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 2001. (Source: Hinrich Foundation)

As a result, the nature of exonumia—such as tickets, vouchers, and tokens—changed dramatically. No longer do these items reflect the elements of the command economy or carry the ideological undertones that characterized the Mao era. Instead, modern exonumia have evolved into symbols of consumer choice and economic freedom, often associated with entertainment, commerce, and tourism. For instance, theme park tickets or shopping vouchers now embody the spirit of leisure and consumerism, in stark contrast to the utilitarian purpose of ration tickets of the past. This shift signifies not just a change in economic policy but also a profound transformation in societal values, where personal choice and market dynamics have taken precedence over state control and ideological conformity.

Home Page