Honors and insignia emerged alongside the very initial emergence of the socio-political hierarchy, the division of labor, and conscious social groups. Honors and insignia often denote the sense of belonging whether it be pertaining to communities or achievements socially, economically, and politically.

Honors and insignia have also evolved and adapted over the years: from the earliest Crown of Sumer and the Crown of Upper Egypt to the development of various coats of arms in medieval Europe, to the flags of the P.O.U.M. flying during the Barcelona May Days of the Spanish Civil War, all the way to the symbolic Mao Badges and "Red Guard" sleeve badges during the Chinese Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution that will be examined on this page.

Globalizing and extending the scope beyond Mao and the "Maoist time-space vicinity", we can also consider the elaborate insignia of the Byzantine Empire, the ceremonial robes worn by monarchs, and the distinctive military decorations introduced during World War I as evidence of the manifestations of honors and insignia over the course of history. Moreover, the use of the Olympic rings as a symbol of unity and competition also exemplifies how insignia can represent broader ideals.

Honors - Achievement and Recognition

Honors in the Mao Era are a complicated topic.

On one hand, Mao and the leadership of the Party (CPC) stressed the importance of using honors of various kinds to commemorate the revolutionary martyrs, award exemplary workers, and, in general, to recognize the contributions made by individuals during the socialist revolution and the construction of the new socialist state. Following this narrative, it may seem that honors would naturally flourish in the Mao Era, perhaps even similar to its revolutionary forebear – the Soviet Union.

Indeed, in the early ages of the People's Republic, China did adopt a Soviet-style honors and decoration system: the Orders and Medals of Bayi, Independence and Freedom, and Liberation (see below for specifics). This resulted in the first wave of honors being issued circa 1955, the same time when the Type 55 Uniform was issued.

However, the elevated status given to medals and honors soon resulted in what Mao viewed as "individualistic heroism" that ran starkly contrary to the "collectivism" of the new socialist state. Consequently, after the initial circa 1955 wave of honor issues, Mao directed the state to gradually decrease its issuing and the importance placed on such awards and honors. Though honors at large remain an integral part of the functioning of Chinese society, their materializations in the form of medals decreased, and they were beginning to be more directed at collectives rather than individuals. Hence, in the late-Mao Era, the honorary titles awarded to factories as a whole compared to a singular worker and to an entire platoon of soldiers instead of a singular soldier became much more common. In Mao's view, this maneuver allowed him to avoid China's descent into the abyss of the appraisal of "individualistic heroism" and allowed it to remain loyal to orthodox Marxist "collectivism". It is also interesting to note that Mao personally refused to be honored and awarded by any formal means. Mao rejected the proposed title of "Grand Marshall of the People's Republic of China" and did not decorate himself with orders and medals, a stark comparison to his Soviet contemporaries such as Stalin, Khrushchev, and especially Brezhnev.

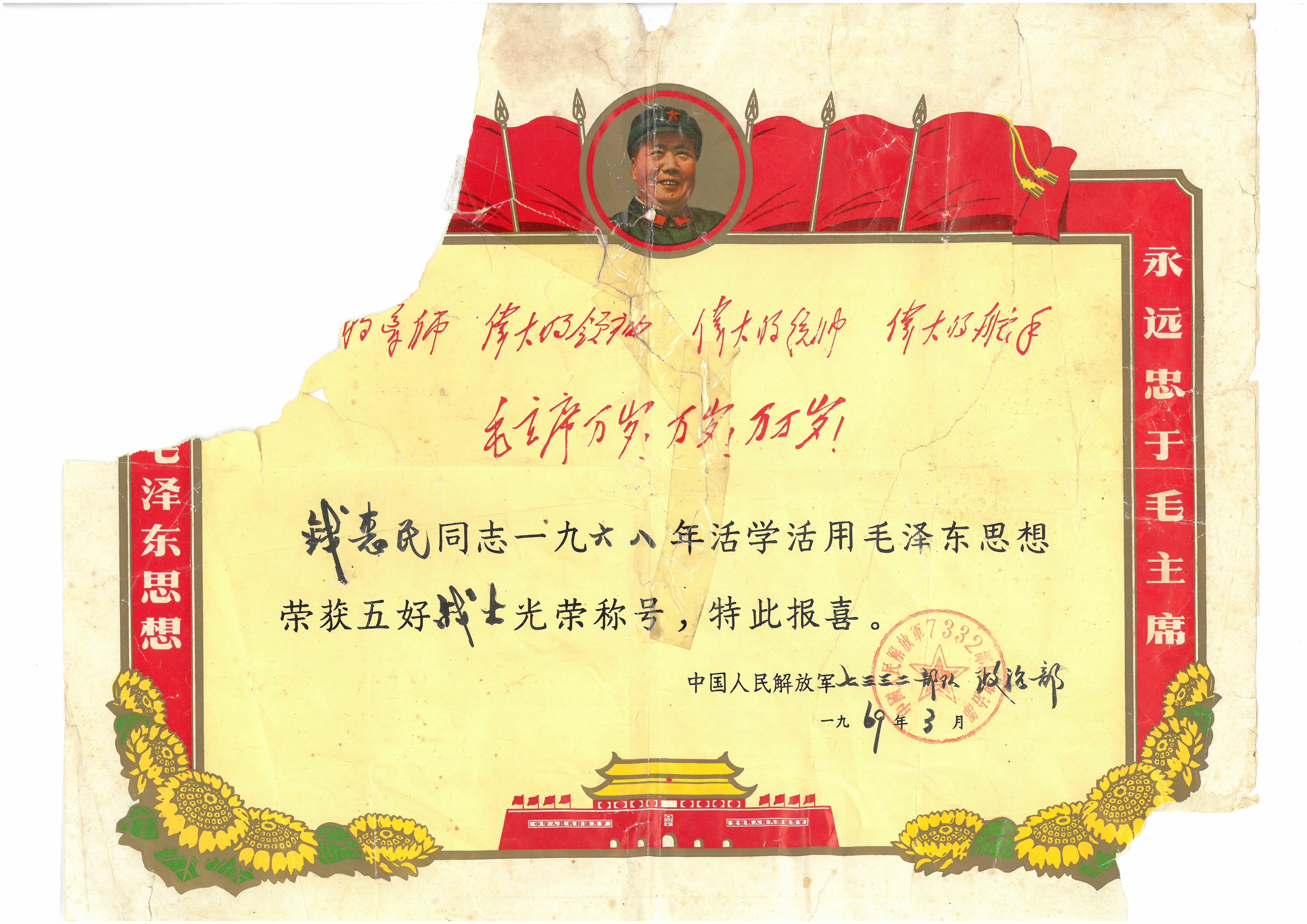

ABOVE. An award certificate of the "Five Good Soldier" dated 1969, awarded to Qian Huimin. The text on the right reads: "Always loyal to Chairman Mao". The top-most text in the center reads "The Great Teacher, the Great Leader, the Great Commander-in-Chief, the Great Helmsman. Long live Chairman Mao!" The main body text of the award certificate reads: "Comrade Qian Huimin is awarded the Five Great Soldiers Honorary Title in 1968 for his flexible learning and active implementation of the Mao Tse-tung Thought". The signature on the bottom right reads: "People's Liberation Army of China, 7332 Unit, Political Department".

ABOVE. Order of Bayi, 1st Class. Issued to all personnel that have made significant contributions to the Chinese Revolution during the early "Red Army" Era. (Source: 58eventer)

ABOVE. Order of Independence and Freedom, 3rd Class. Issued for valiant combatants during the Second Sino-Japanese War. (Source: Hunan Museum)

ABOVE. Order of Liberation, 3rd Class. Issued to honor the heroes and combatants of the Second Chinese Civil War. (Source: Chinese National Museum of Women and Children)

ABOVE. Commemorative Medal of the Victory in the Korean War. (Source: Sina Collection)

Mao's directives left China with an almost blank slate regarding its honors system and culture. After Mao's death and the subsequent end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the honors system was largely restored. The Meritorious Service Medal was immediately restored and began its issue in the Sino-Vietnamese War to those who had demonstrated exceptional military merit and service. Gradually, China's honors system and culture are being built, aligning itself more with the practices of other nations.

ABOVE. (Right) Meritorious Service Medal, 3rd Class. (Left) Meritorious Service Medal (1st Class) being awarded to the soldiers in the Sino-Vietnamese War, cinematic representation from the film "Wreaths at the Foot of the Mountain" (1984).

Insignia - Memorabilia of Identity and Belonging

Comparatively, the insignia of the Mao Era flourished, especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Almost all of the insignia of the Mao Era in some way or another related to Mao personally or to Mao’s political directives. As a result of this, openly displaying and wearing such insignia in the Mao Era became a vital means for the average layperson to display their political views and loyalty to the socialist revolution. These insignia took many forms, the most prominent including but not limited to: badges, armbands, and apparel (please see the page “Apparel” for more information).

Mao Badges (i.e., badges that feature Mao, usually in the form of a bust), perhaps the most prominent insignia of the Mao Era, can trace their emergence back to 1932 in celebration of Mao’s appointment as the Chairman of the Chinese Soviet. The first wave of Mao Badges and other Mao-related insignia appeared in the 1950s, shortly after the establishment of the People’s Republic of China. Many corporations, which have yet to be nationalized and collectivized, especially jewelry stores, made Mao Badges of their own to indicate their loyalty and allegiance to the CPC and Mao. Scholarship estimates that Mao Badges made in the 1950s account for around 10% of all Mao Badges made.

ABOVE. A collection of three Mao Badges from the Cultural Revolution (Left to Right: "Loyal; Long Live Chairman Mao!; *870*" Mao Badge, Ceramic Mao Badge "Jing De Zhen, China", and "Long Live Chairman Mao!; South Sea Fleet; 1967" Mao Badge)

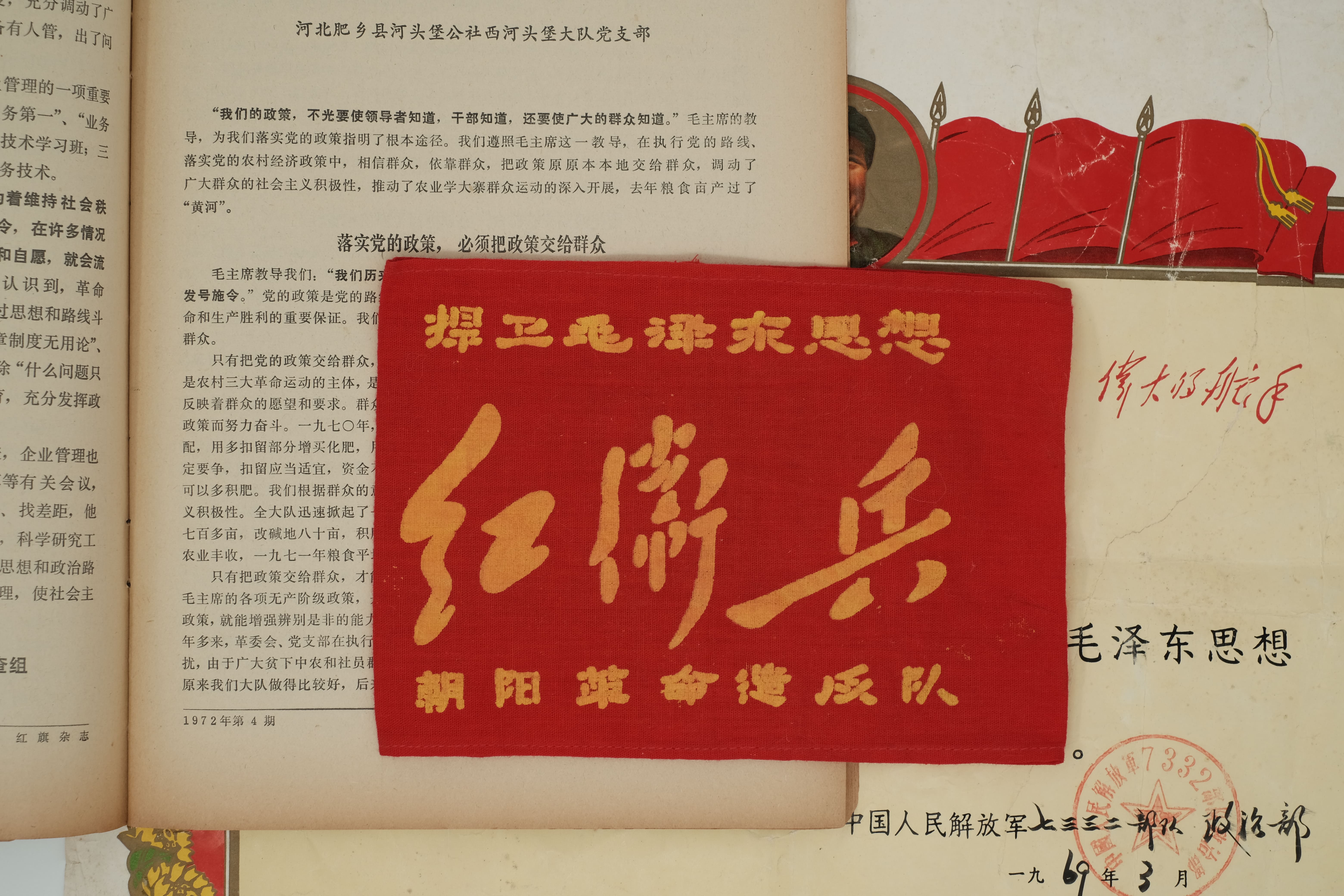

The Red Guard armbands were a significant symbol during the Cultural Revolution. Worn by members of the Red Guards, predominantly youth and students, these armbands served as a badge of ideological commitment to Mao Zedong's revolutionary ideals. Typically made of red cloth, they featured slogans and insignia that promoted communist thought and loyalty to Mao. The armbands distinguished Red Guards as active participants in the movement, empowering them to challenge authority and attack perceived bourgeois elements within society, including teachers, intellectuals, and party officials. This fervent activism contributed to widespread chaos and violence, as the Red Guards sought to purify Chinese society of "counter-revolutionary" influences. The armbands became emblematic of the radical spirit of the time, reflecting the fervor of youth.

ABOVE. Original Red Guard armband (Beijing) from the Cultural Revolution (The background is a mini-historical recreation scene with a contemporary publication and a certificate)

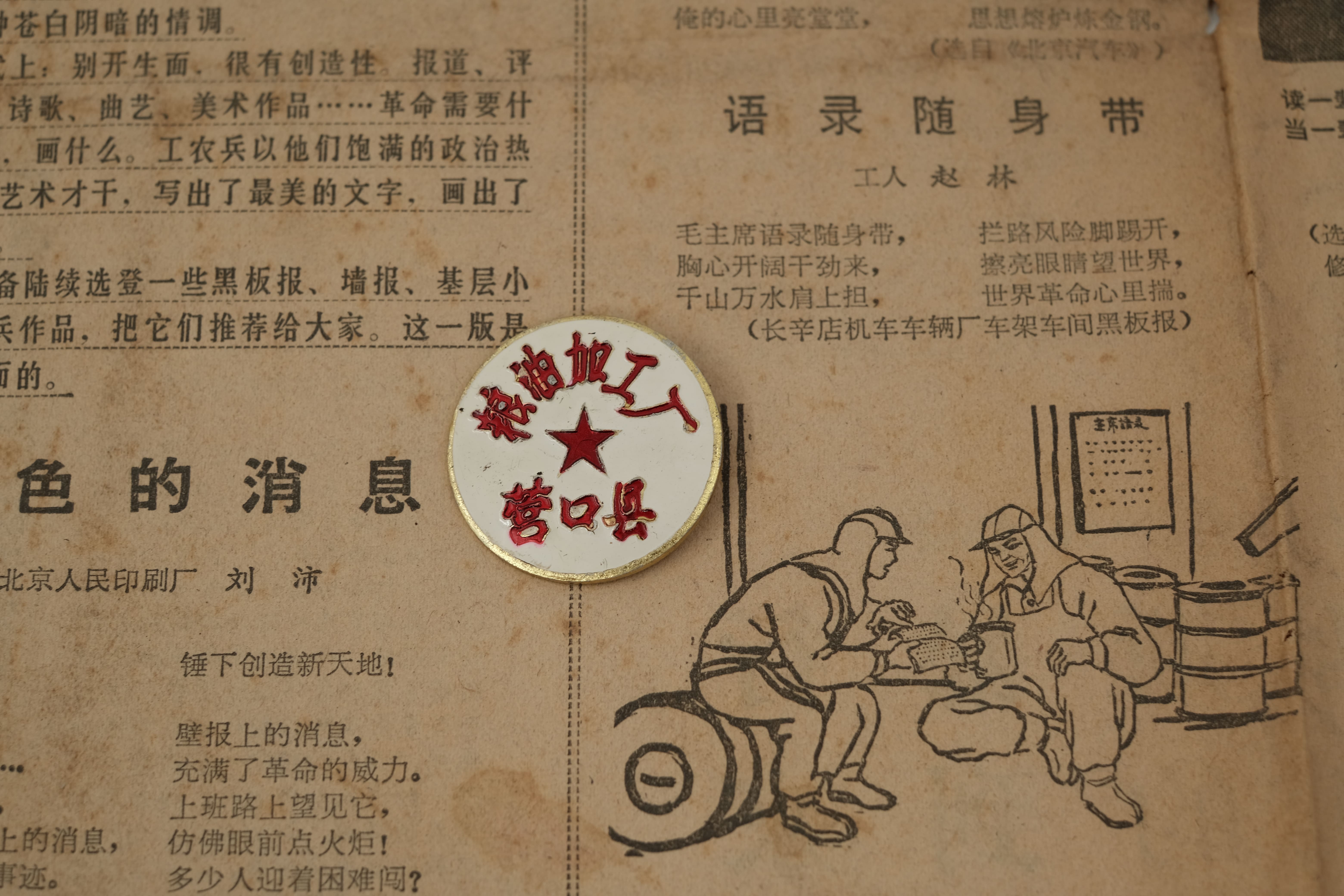

Factory workers were given badges, reflecting the Mao Era’s commitment to honoring and giving importance to the industrial proletariat and their role in building a socialist future. However, this practice diminished in the post-Mao Era as the Communist Party shifted away from rigid ideological commitment and rhetoric.

ABOVE. A factory badge from the Mao Era, No. 446 (The background is from a contemporary newspaper that features discussions regarding the Mao Tse-tung Thought)

The frenzy revolving around Mao Badges truly exploded during the Cultural Revolution. Scholarship estimates that around 90% of all Mao Badges and other Mao-related insignia were made during the Cultural Revolution. It is estimated that between 1966 and 1968, over 8 billion Mao Badges were made. At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Mao Badges were still a relatively new concept and few wore them daily. However, in 1967, the PLA formally issued a standard Mao Badge to all officers and soldiers, causing a surge in the popularity of Mao Badges. In 1969, the wearing of Mao Badges reached a peak with an estimated 94% of the population wearing Mao Badges. This trend gradually declined after the 1970s as Mao personally directed the “cooling-down” of the Cultural Revolution to refocus the nation, to a certain extent, on economic production.

ABOVE. Young girl dressed in soldier attire with a Mao Badge at the arrival of the press plane in Peking, China - NARA (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Though Mao expressed great concerns regarding the negative influence of "individualistic heroism" regarding the issuing of honors, Mao was able to create an immense "cult of personality" revolving around the Mao Badge. However, Mao personally expressed disdain for the widespread zeal for Mao Badges and other Mao-related insignia. Mao, Chou, and other high-ranking officials of the CPC viewed the mass production of Mao Badges as a waste of materials in a time when the state was in dire need of materials for economic development. In 1969, the Central Committee issued regulations regarding Mao Badges and other Mao-related insignia, claiming that Mao Badges had become overly formalistic. This resulted in a gradual decline of the presence of Mao Badges, all the way to its de facto termination of its status after the end of the Cultural Revolution. In present-day society, Mao Badges have somewhat made a return and are experiencing an increase in popularity among the leftist youth, though this trend remains rather insignificant.

ABOVE.A side-by-side comparison of Communist Youth League of China badges. The left and the better crafted (copper enamel) belongs to the Mao Era, while the right and the less well-crafted (aluminum paint) belongs to the post-Mao Era, testifying the decline of ideology in the post-Mao Era.