Numismatics, in narrow terms, refers to the collection and study of coins, paper currency, and other closely related pieces of exonumia. In broader terms, it could be expanded to include medals, orders, and badges, though Mao Era Garbology does not adopt this latter definition.

The study of numismatics offers collectors and historians a unique lens through which to examine the multifaceted dimensions of history. On one level, coins and currency serve as tangible records of economic development, providing insight into "monetary history" by revealing patterns of trade, inflation, and fiscal policy across time periods. The materials, denominations, and minting techniques employed in coinage can also be indicative of the economic priorities and technological advancements of a society. Beyond their economic significance, numismatic pieces also function as cultural artifacts, being purposefully crafted to reflect the social and political Zeitgeist of their era by the authorities. The artisanal details such as inscriptions, symbols, and iconography can delineate societal values, political agendas, and historical events — whether celebrating victories, promoting unity, or commemorating certain events. Even the choice of imagery, such as allegorical representations or national emblems, can reveal how a state wished to be perceived both domestically and internationally.

The official currency of the People's Republic of China is the Renminbi (RMB), which translates to "the people's currency." The RMB operates on a decimal system, with values increasing in multiples of ten. It consists of three main units: the Fen (cent), the Jiao (equivalent to a dime, or 10 Fen), and the Yuan (equivalent to a dollar, or 10 Jiao). This tiered structure facilitates everyday transactions and reflects China's modern monetary system.

Numismatics - The Third Series of RMB 1962

The planning of the Third Set (Series) of RMB began in 1955 to replace the Second Set (Series) of RMB. The planning progress accelerated in 1959 after the People's Bank of China made a formal presentation to the State Council. The Third Series of RMB was finalized and then progressively introduced to the market from 1962 to its gradual replacement by the Fourth Series of RMB in 1987, eventually being completely phased out of the market in 2000 with a circulation history of 38 years.

The Third Series of RMB included the following denominations: 1 Jiao, 2 Jiao, 5 Jiao, 1 Yuan, 2 Yuan, 5 Yuan, and 10 Yuan. Currency with the Fen (cent) unit, namely 1 Fen, 2 Fen, and 5 Fen, from the Second Series of RMB continued in circulation and print, but as it was not considered a new design, it is not in the official catalogue for the Third Series of the RMB. Additionally, minted coins were also a part of the Third Series of RMB, with denominations of 1 Fen, 2 Fen, and 5 Fen. Another series of minted coins appeared briefly in the 1980s known as the "Great Wall Coins" (Chinese pinyin "Changcheng Bi") that featured the Great Wall of China as its reverse engravings on its 1 Yuan Coins. It featured the denominations of 1 Jiao, 2 Jiao, 5 Jiao, and the titular 1 Yuan.

Comparatively, the Third Series of RMB possesses stark aesthetic orientational qualities that are reflective of the socio-political zeitgeist as well as the political agenda of the CPC in the 1960s, the time of its release.

The portrayal of labor, intended to glorify the working class ("proletariat" in Marxist gobbledygook) was a common theme among the Third Series of RMB, reflecting how Mao, and other members of the CPC, intended to advance the construction of socialism via accentuating the glory in labor and in one's class label being a progressive "proletariat". This was in line with the strengthening of the democratic people's dictatorship during the 1960s and carrying on into the 1970s, where Mao and the CPC stressed that the proletariat must retain control over the means of production and ownership over the state machine to prevent revisionism by reinstating purity of Marxism-Leninism in China.

Top to Bottom:

1 Jiao, 2 Jiao, 5 Jiao

Top to Bottom:

1 Yuan, 2 Yuan, 5 Yuan, 10 Yuan

On the individual level, each denomination bears a unique printed image:

- 1 Jiao - Farmers walking out into the fields to begin labor.

- 2 Jiao - The Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge that began construction in 1955 and completed construction in 1957. The Wuhan Yangtze River Bridge was the first bridge that spanned across the Yangtze River, bringing an end to the era where railways in northern China and southern China had to be connected via cross-Yangtze-River ferries. The completion of the bridge was seen as a major industrial achievement of socialist construction, greatly boosting national morale and confidence in the early Republic years.

- 5 Jiao - Female textile workers working in the factories. The portrayal of female figures symbolizes how the status of women underwent fundamental changes in the Mao era – women were increasingly liberated from their domestic responsibilities and highly encouraged to pursue industrial work on equal grounds as their male counterparts. However, there still existed a disparity with the industrial work that the two genders pursued, in that it was more common for men to work in "harder" industries such as metalwork or manufacturing while women found work in "softer" industries such as the textile industry.

- 1 Yuan - Female tractor driver in the agricultural sector. Though there was still a gender disparity in the industrial sectors, it was no longer an issue in the agricultural sector, where women and men stood on equal obligations, responsibilities, and opportunities to work the same as men.

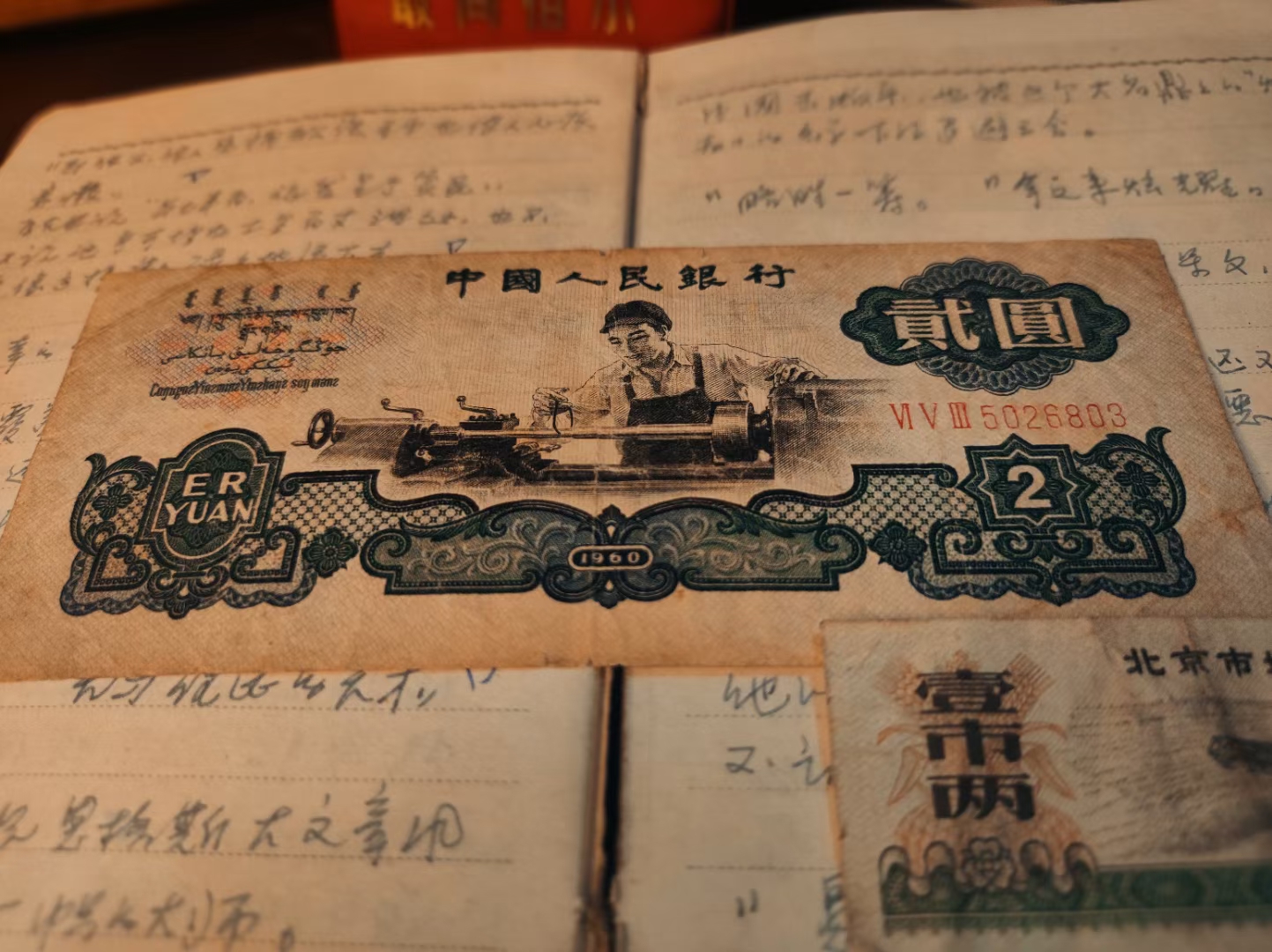

- 2 Yuan - A continuation of socialist realism in portraying the average worker.

- 5 Yuan - A steelworker meticulously attending his work in steelmaking. Steel production has been, and still remains, a major indicator of the industrial capabilities of a country. As early as 1958, during the Great Leap Forward, Mao proposed that China's steel production should "surpass Britain in 15 years and surpass the US in 50 years", exemplifying the pedestal of importance given to steel production. Many historians critique Mao's idealistic goal in attempting to quickly surpass Britain and the US in terms of steel production as being unrealistic, yet in reality, China's steel production was able to approximately catch up with that of Britain's in 15 years and China was able to surpass the US in terms of steel production in just 38 years after the goal had been set by Mao. Nevertheless, the inclusion of steelmaking on currency serves as a reminder by the state to the average citizens of how industrial development still serves as the cornerstone of overall national prosperity.

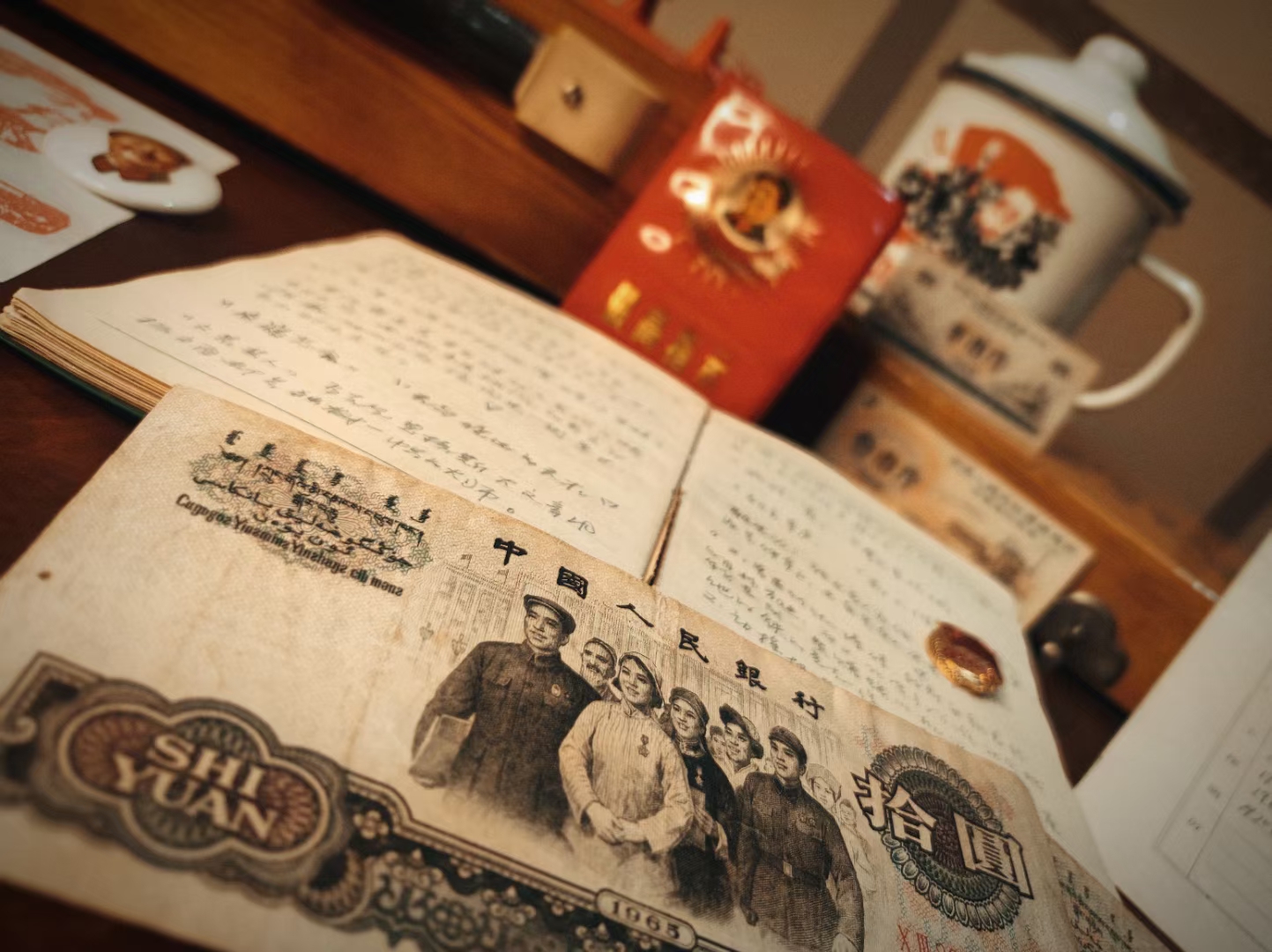

- 10 Yuan - An eye-level mid shot of a collective proletariat portrait. The 10 Yuan note came to be nicknamed "Great Unity" due to its portrayal of proletarian unity, underscoring the state's consideration of propagating the value of national and class unities in order to prevent rifts from developing between groups that may give rise to national fragmentation.

The idea of proletarian unity also comes into play. The lesser denominations all portray individual laborers in specific settings, but when they are put together, they form a collage that resembles an exhibition that highlights the theme of the glorification of labor. The idea of it forming a collage is evident in the highest denomination 10 Yuan being nicknamed "Great Unity" as it portrays the different ethnic groups and the worker, farmer, and soldier (the three main proletarian careers in the Mao era) in China, subliminally underscoring to the reader the importance of maintaining national, class, and cross-ethnic unity in China.

Historical recreation photograph, including the Third Series of RMB 2 Yuan note

Historical recreation photograph, including the Third Series of RMB 10 Yuan note

Numismatics - The Fourth Series of RMB 1987

After the Open and Reform Policy of 1978 spearheaded by Deng Xiaoping, China's socio-economic and political landscape renewed. In the new directive to open the country up to foreign investment and to "learn the advanced experiences of foreign countries", revolutionary socialism (i.e., Maoism, especially under the context of the Cultural Revolution) was stalled. This was reflected in the newly issued Fourth Series of RMB.

The Fourth Series of RMB was released in 1987 and featured the following denominations: 1 Jiao, 2 Jiao, 5 Jiao, 1 Yuan, 2 Yuan, 5 Yuan, and 10 Yuan, 50 Yuan, and 100 Yuan. Despite the party's quasi-renunciation of orthodox socialism and the cult of personality of Mao, the Fourth Series of RMB was the first series of RMB to feature a portrait of Mao Zedong on its currency on the 100 Yuan note.

The Fourth Series of RMB (1987) - Top to Bottom (Left to Right) - 1 Yuan, 2 Yuan, 5 Yuan, 10 Yuan, 50 Yuan, 100 Yuan (1 Jiao, 2 Jiao, 5 Jiao are included in the comparative image below)

The Open and Reform Policy brought China into an era of unprecedented growth, resulting in an increase in real GDP (the level of output of the economy) and demand-pull inflation, which is generally considered healthy inflation for a country's economic development. As price levels increased and subsequent wage increases, the previous 10 Yuan notes were unable to support large monetary transactions and therefore birthed the 50 Yuan and 100 Yuan notes. Both of these notes serve as memorabilia of the growing economy in the post-Mao era and an increasing material quality of life (supported by the abundance of products on the market and increasing household incomes). However, perhaps with this economic growth and the abolition of the portrayal of proletarian glory and unity and the fairness-oriented Maoist framework, China's inequality and corruption soared in the early years of the Open and Reform Policy, eventually evolving into the political turbulence of the late 1980s.

Extending this idea, as "class struggles" was no longer the dominant political narrative, national unity became the new underlying theme of the Fourth Series of RMB. To this end, figure selection became more based on showcasing the cultural diversity and cross-ethnic unity in China, attempting to strengthen the unified national image and collective identity. This was the case for the following denominations: 1 Jiao, 2 Jiao, 5 Jiao, 1 Yuan, 2 Yuan, 5 Yuan, and 10 Yuan notes.

Particularly interesting artifacts, the 50 Yuan and 100 Yuan notes took on a more traditional politically-oriented manner to bolster the notion of national unity and the idea of a national identity. The 50 Yuan note featured three symbolic figures (left to right) – the intelligentsia, the farmer, and the worker – that represented the social constituency of Chinese society at the time. By arranging the three figures in tandem, it conveyed a sense of collective solidarity and unity across the different sectors, and as all three sectors still possessed heavy influence from the social landscape of the Mao era, it can be seen, to some extent, as the swansong numismatic piece that still carries the last remaining orthodox socialist ideals. On the other hand, the 100 Yuan note featured the portraits of four state and party leaders (left to right) – Zhu De, Liu Shaoqi, Chou Enlai, and Mao Tse-tung. The particular inclusion of Liu in tandem with Mao is reflective of the party's stance towards the late-Mao era (i.e., the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution) where it now denounced the zealous attempt at "perpetual revolution" via the Cultural Revolution. In essence, it is symbolic of the party acknowledging Liu's theory of letting capitalism develop first was not a "wrong line", providing ideological and authoritative foundations for the Dengist Open and Reform Policy.

Comparative between Third Series of RMB and Fourth Series of RMB (Please zoom-in for detailed view):

Top to Bottom:

1 Jiao, 2 Jiao, 5 Jiao

Top to Bottom:

1 Yuan, 2 Yuan, 5 Yuan, 10 Yuan

Numismatics - The Fifth Series of RMB 1999

After Deng's southern visit in 1992, China's liberalization of the economy continued, entering what would be considered the fastest economic growth window China (and the world) will ever see. With such growth came increasing exports and imports, and in this increasingly interconnected world, the Fourth Series of RMB became obsolete as it was not considered to be instantly recognizable on the international market. Thus, a currency that possessed more recognizable Chinese characteristics went under design.

Eventually, Mao was decided as the most recognizable Chinese figure to be printed on the Fifth Series of RMB. Differing from the Fourth Series of RMB, Mao was featured all the denominations. The reverse of each of the bills featured a site of nature or those with humanistic value, demonstrating the balance between economic growth and the retention of tradition and nature.

The Fifth Series of RMB included the following denominations: 1 Yuan, 5 Yuan, 10 Yuan, 20 Yuan, 50 Yuan, and 100 Yuan. The 2 Yuan denomination was canceled and the 20 Yuan denomination was added. Additionally, the Fifth Series of RMB continued using the 1 Jiao and 5 Jiao bills from the Fourth Series of RMB with no new designs being made. The 2 Jiao bill was cancelled. This is further evidence of healthy demand-pull inflation that occurs with the natural increases in price levels as the economy grows, demonstrating overall economic growth and development of China.

Top to Bottom:

100 Yuan, 50 Yuan, 20 Yuan, 10 Yuan, 5 Yuan, 1 Yuan (Source: Baidu)

Focused view of the 100 Yuan note, nicknamed "red Mao" (Source: Baidu)

Though the cult of personality of Mao was much denounced after the 3rd Plenary Session of the 11th CPC Central Committee, its somewhat re-emergence in numismatics testifies to the enduring legacy of Mao both domestically and internationally. Domestically, Mao's status as the savior of China and the Chinese people remains unchanged, and all political power still, to a large extent, stems from Mao. Internationally, Mao remains to be the most recognizable Chinese figure and a beacon of the remaining revolutionary ideals of China.

Conclusion

The study of numismatics reveals that coins are far more than mere currency—they are miniature canvases of history, capturing the essence of their time. Through their designs, materials, and inscriptions, they reflect the political ambitions, cultural values, and economic realities of the societies that minted them. Like echoes of the Zeitgeist, these small yet profound artifacts allow us to trace the evolution of the Chinese social, economic, and political landscape, offering a tangible connection to the past. As we examine these fragments of history, we are reminded that material culture serves as an indispensable lens through which we can interpret the grand narratives of human experience. This exhibition has invited us to appreciate how something as commonplace as currency can unlock profound insights into the world that shaped it—and, in turn, the world it helped shape.

Home Page