Inheriting the fundamental Marxist-Leninist principles, Mao perceived literature, publication, and art as dependent upon the political edifice, but also, in reverse, greatly impacted the political edifice. Mao firmly believes that all literature and art (Chinese: wen yi) must “serve the people”, particularly that it must serve the workers, the peasantry, and the soldiers. Mao stressed that publications were among the most important frontlines in which socialism would have to defend against the influences of liberal capitalism, and hence, Chinese publications in the Mao Era became increasingly politicized.

By the eve of the Cultural Revolution, epitomized in the hiatus caused by the work “Hai Rui Dismissed from Office”, Mao became increasingly dissatisfied with the status of Chinese literature and art. Mao believed that, at the time, the “decadence of capitalism” had begun to establish a foothold in the literature and the arts, allowing for the potential subversion of the Chinese state and its socialist system. From Mao’s perspective, the Chinese literature and arts at the time still centered itself on the old narrative of “talented scholars and beautiful women, and the kings, lords, generals, and ministers” instead of “serving the people”.

Mao was committed to changing the status quo, and in doing so, he would initiate his most controversial political movement – the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). As the name suggests, the Cultural Revolution was not about grandiose political struggles, rather it was inherently “cultural”. The original motives of the movement were nothing more than to reclaim the frontline of the literature and arts back into the hands of the proletariat, and all other forms the political movement later took on stemmed from this fundamental purpose.

Publications - Politicization

Indeed, much of the publications during the Mao Era were increasingly politicized, reflecting Mao’s intent to use information to shape public consciousness and to safeguard the ideological support for socialism in China. Political news dominated the headlines, with stories often focusing on the successes of the socialist revolution, the achievements of the working class, and the denunciation of perceived enemies of the state. This emphasis on political content served to reinforce party ideology and to align discourse.

More iconically, the inclusion of the "Quotations of Chairman Mao," became a hallmark of nearly all publications. The “Quotations of Chairman Mao” was also published as a small, pocket-sized book, which was filled with Mao's directives on various topics, from revolution and class struggle to personal conduct and morality. Its widespread distribution meant that it accompanied readers in their daily lives, influencing thoughts and actions at every level of society. The presence of Mao's quotations in newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets underscored the notion that his ideas were not just political doctrine but also essential guidance for personal behavior. The following are a series of publications from the Mao Era:

Beijing Daily, April 20, 1966 Newspaper. The headline news reads "After friendly visits to East Pakistan and Myanmar, Chairman Liu (Liu Shaoqi) returns to Kunming with a warm welcome." It is also interesting to note that weeks after the publication of this paper, the Cultural Revolution would begin, and Liu would be targeted as a "capitalist roader". The other news on this page all concern the revolutions and struggles of the oppressed around the world, demonstrating the Mao Era's upholding of its internationalist obligations.

The opening pages of a "Red Flag" party magazine. The left page includes a quote from Lenin, while the right page includes a quote from Chairman Mao. Both quotes concern the topic of the dictatorship of the proletariat, demonstrating the Mao Era's use of publications to disseminate its political ideology.

An excerpt from the Study Guide of Marx's "The Civil War in France". There were a series of study guides published during the Mao Era, particularly during the Cultural Revolution, on the classical Marxist-Leninist theoretical works. During the Cultural Revolution, studies on Marxism-Leninism and the Mao Tse-tung Thought were nearly compulsory and integral to political life.

An article titled "Committing Everything to Serve the Interest of the People - A Study of 'Serve the People' [one of Mao's classics]. This further illustrates the wide scope in which Mao hoped to propagate the socialist view in Chinese society, in an attempt to prevent "revisionism".

An excerpt from the Party Magazine "Red Flag" 1975. All the bolded text within the article are exact quotations from Chairman Mao. The frequent quoting of Mao in publications testifies his political significance and his attempt to solidify socialist ideology and values in Chinese society.

An excerpt from the English version of Lenin's "The State and Revolution". It is worth noting that the quality of the book far outranks those published in Chinese. This reflects the wider practice at the time of upholding China's internationalist obligations, which involves saving domestically to give the best and most to the revolutionary causes around the world.

An excerpt from the Party Magazine "Red Flag" 1972. The left page is a Quotation of Chairman Mao. The right page features a party editorial titled "Unite, for Greater Victory". It is worthy to note that official party editorials were commonplace during the Cultural Revolution as means of propagating party policy. Their usage and importance decreased gradually after 1978, however.

An excerpt from a mathematics textbook published during the Cultural Revolution. The text in bold are all Quotations of Chairman Mao. The one on the left page reads, "The masses have infinite creativity", while the one on the right page reads, "a departure from specific analysis means that we can no longer understand the characteristics of any contradictions". The inclusion of Mao and ideology in early education is further emblematic of the party's attempt at reinforcing China's (and its society's) ideological stance and firmness.

Publications and Praxis - Juxtapositions Across Time (the Post-Mao Era)

The pragmatic political concerns of establishing connections with the liberal West meant a gradual termination of the Quotations of Chairman Mao in publications. The post-Mao party believed that to build cordial ties, its Marxist-Leninist and Maoist rhetoric must be dimmed. The iconic party magazine “Red Flag” also completed its historical mission in 1988, and was succeeded by the new party magazine “Seeking Truth”, aligning much with the gradual diminishing of ideological rhetoric.

An image widely circulating in the Chinese internet that depicts a juxtaposition of party rhetoric across time. The upper image is a classic Cultural Revolution Era slogan, "Working men of all countries, unite!". The lower image is a post-1978 reform (post-Mao) era slogan, "Time is money, efficiency is life". This stark disparity between the publicized rhetoric testifies the tremendous change experienced by China after Mao's death.

A series of "Seeking Truth" articles published regarding the theories of President Xi. "Seeking Truth" retains its functions to disseminate ideology, but its zealousness has greatly decreased in comparison to the "Red Flag" of the Cultural Revolution times.

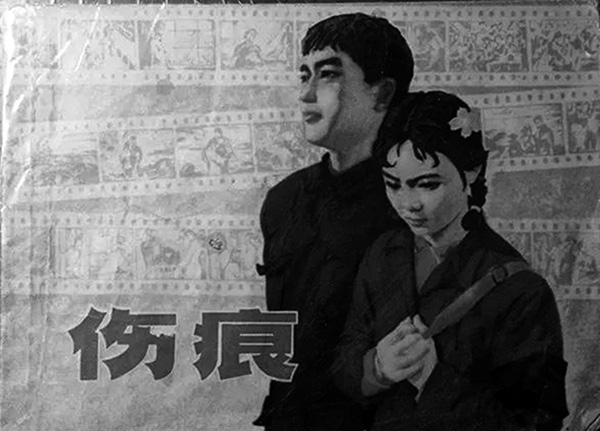

Also, as a result of the Mao Era's heightened politicization of publication, literature, and the arts, much of the literature and art community expressed dissatisfaction toward their perceived deprivation of intellectual and creative freedom. A new wave of literature emerged with Lu Xinhua’s 1978 story “Scar” that targeted hypocrisy and corruption in the party, and this new wave of literature was coined with the name “Scar Literature” or “Literature of the Wounded”. A common thread of “Scar Literature” is that it focuses on the various perceived injustices that occurred during the Cultural Revolution, particularly toward the intelligentsia, who were often required to complete labor and reeducation by the peasantry in the rural areas. “Scar Literature” remains a controversial topic in modern-day China. Supporters believe “Scar Literature” symbolizes an important step where the country was able to rightfully reflect on its wrongdoings. Detractors claim that “Scar Literature” is either (1) a personal attack on Chairman Mao and is reactionary in its intent to fundamentally subvert socialism in China; or (2) an exaggeration by the intelligentsia, because in a majority of the cases, when the intelligentsia did get sent to rural areas for labor reeducation, they were given the best food and accommodations the locals could offer, even better than what the locals themselves consumed and lived in daily.

The cover of "Scar" by Lu Xinhua, published in 1978. The book is among the first to openly reflect on the potential limitations of the Cultural Revolution, particularly on the intelligentsia. (Source: The Paper)